According to some public education advocates, charter school administrators target troublesome, learning-disabled, or otherwise low-performing students and suspend or expel them disproportionately in order to improve their school’s aggregate test scores. These fretful advocates mean well, but a new analysis from CER’s research team shows that they are ultimately misguided. When it occurs, this effect is often unintentional and simply the result of low performance and other factors being correlated, but some critics take a more cynical stance and see active manipulation. If manipulation of disciplinary systems were found to be a major reason for increased charter school performance, this would conveniently undermine the legitimacy of the operational freedom that charter schools enjoy on matters such as discipline.

A recent Washington Post article examined charter school expulsions in the District of Columbia. DC Public Schools adopted a uniform discipline policy in 2009 that permits expulsion only for severe violations, such as bringing a gun or drugs to school or assaulting students or staff, but charter schools may set their own policies. Of the approximately 76,700 students enrolled in DC Public Schools in 2011, about 29,300 attended charter schools. Despite only enrolling 38% of DC students, charter schools expelled 676 students between 2009-2011, compared to 24 expulsions in public schools. This gross discrepancy seems damning at first glance, but it is possible that DC charter schools both discipline more students and earn higher test scores independent of this fact. The Post article uses a blunt cross-sectional comparison that does not allow us to test this hypothesis. However, we can use student achievement data to see whether the test score advantage that DC charter schools have over traditional public schools (TPS) is larger than the possible gain that could come from disciplining only poor-performing students.

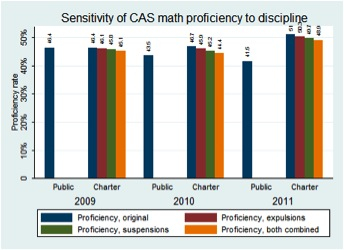

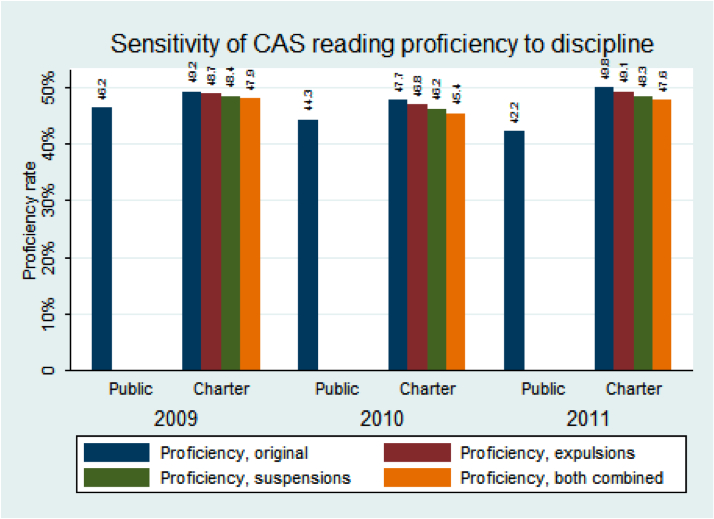

CER Research Associate Kai Filipczak performed a sensitivity analysis of charter school proficiency rates in DC using test score data from 2009 – 2011. Instead of comparing raw numbers of disciplined students (which ultimately says nothing about student learning), this technique uses disciplinary data to artificially lower the number of proficient students at a charter school. The analysis estimates charter school performance very conservatively, and allows us to make a meaningful comparison between TPS and charters in what is effectively the “worst case scenario” for charter schools. (For more details, see the full write-up in the Georgetown Public Policy Review.) Charter schools retained their advantage over public schools in every year and subject where charter school performance was initially greater than TPS performance. Even after artificially lowering the proficiency rate to account for disciplined students, DC charter schools are still 2.47 percentile points more proficient in math and 2.65 points more proficient in reading on average. Furthermore, the actual change in proficiency rates as a result of making stringent disciplinary assumptions was small in absolute terms: at most, the charter school proficiency rate changed by about 2.4 percentile points. While some individual schools expelled many students (for example, one school expelled 68 students in a single year), 37% of charter schools went an entire school year without expelling any students.

Charter schools discipline their students in different ways, and so it is grossly unfair to assume that most charter schools have pronounced issues with discipline. It is more reasonable to conclude that a handful of charter schools have questionable practices that deserve further scrutiny, but that the performance of DC’s charter schools as a whole cannot be simply due to disciplinary policies. Selection bias is still a pertinent issue for comparing the effectiveness of TPS and charter schools, but there is little evidence that DC’s charter schools expel students or put them on long-term suspension in order to improve proficiency.

Chicago Public Schools recently revised its discipline code to lessen the use of “punitive” disciplinary policies like automatic suspension and expulsion. Schools operated by the Noble Street Charter Network have been heavily criticized by Chicago activists for high rates of expulsions, as well as for unusual discipline practices, such as fining students for infractions. Charter schools in other districts may indeed be expelling a disproportionately large number of students, but these results should encourage critics of charter schools to be open to the possibility that these schools may also have high performance independent of this fact. Further research is necessary to examine discipline and proficiency in other districts and policy environments, and Chicago Public Schools would be an excellent subject.

In the meantime, it is reckless and unfair to insist that charter schools typically increase achievement through manipulation of discipline policies. The aim of education is to impart knowledge and a variety of skills, and honest reformers should not be wedded to geographically-assigned public schools and their traditions as a means of delivering this content. Is it really so hard to believe that alternatives to traditional public education can achieve stellar results without gaming the system?