17th Edition March, 2017

Since 1996, CER’s yearly scorecard and ranking of state charter school laws has provided guidance and feedback to policymakers on the relative strengths and weakness of charter school policies and their effectiveness in fulfilling the true meaning of the words “charter school law,”— i.e., paving the way for high numbers of strong, autonomous, healthy charter schools, that provide meaningful opportunities for families and their children, and the chance for innovation for all involved.

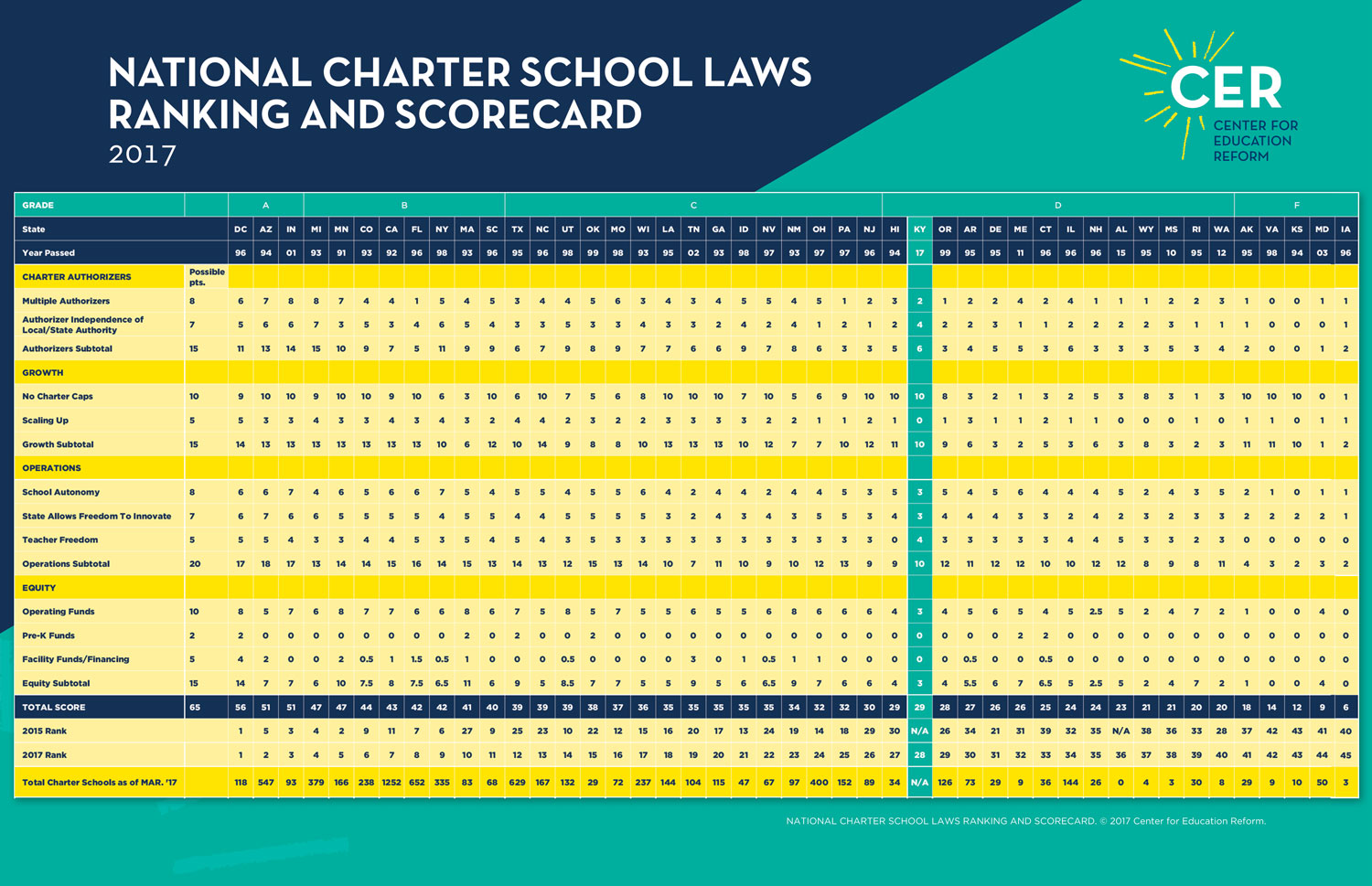

Sixteen successive reports were based on a variety of criteria first designed and validated by the pioneers of chartering. Each year, the national rankings established by CER have not only predicted how a particular law might work in practice, but presented a real-time evaluation of whether, and how, charters are able to operate given the freedoms or restrictions embedded in law. The rankings and corresponding analysis are grounded in the principles and intent of chartering. We review whether a state’s charter school law:

- establishes the ability for citizens to create schools that are independent, in oversight and operations, from the traditional school bureaucracies;

- gives schools wide latitude to operate and innovate without onerous administration rules and regulations dictating what they can do and how they do it at every turn;

- and provides parents with an expansive amount of options from which to choose the schools that best meet the needs of their students.

We are now well into the third decade since Minnesota passed the first state charter statute. The number of charter schools has continued to increase each year at a steady but relatively slow pace. But this past year, that growth abruptly came to a near halt. Overall, the nation’s nearly 7,000 charter schools still serve a fairly small percentage of the total number of students receiving public education, roughly six percent. Some states and cities have far more market share and point the way to what healthy expansive choice does for the whole of public education.

Overall, the impediment to consistent, sustained growth of charter schools is that most state officials view charters, or other school-choice policies, as a core strategy of education reform. National and state top-down policies, intended to broadly impact all public school students or teachers in a state—whether standards and testing, teacher evaluation/compensation, or other efforts—continue to be perceived as the main action, often engendering fierce debates and then later being abandoned after a number of years. Yet, overall improvement in U.S. student achievement on the National Assessment (NAEP) is minimal at best and American students are not closing the gap with our top international competitors.

CER noted in its 2015 report that while “…demand [for charter schools] continues to outstrip supply…” there has been a “lack of progress made in state houses across the country over the past few years to improve the policy environment for charter schools” and, more specifically, “… it is abundantly clear that little to no progress has been made over the past year…”.

In recent years, there has been significant attention—especially, but not exclusively, among authorizers—on a perceived need to focus on charter “quality over quantity”. The strategies discussed have included more stringent approval processes as well as “culling the herd” during charter renewal to let only those schools deemed strong performers continue.

This year, the movement crept to a near halt, a result of these very ill-conceived state policies and what is being termed “regulatory reload.” There is widespread evidence of creeping regulatory intrusion in decisions regarding academic programming, curriculum, discipline, and teacher qualifications. The problem, it appears, is policymakers who are given numerous recommendations no longer know the difference between policies that advance the cause of effective charter schools and those that strangle them.

But are charter regulators really the key actors in improving the quality of teaching and learning in charter schools? We see no evidence of that. In keeping with CER’s historic values and philosophy, which guided the strongest charter school laws, we have introduced some new elements to better reflect the policies to which states should aspire. By focusing on achieving perfect scores in four critical areas, states can reverse the encroaching isomorphism – the inexorable push to make all schools look and operate similarly – and spawn the kinds and quantities of schools that truly put students on a path to access exceptional educational opportunity. Those elements are based on the following principles:

Multiple Authorizer Independence: Multiple authorizers remain critical, but almost as critical, is the independence of those authorizers. A new trend since the 2015 analysis is the prevalence in states of entities we call “uber authorizers,” newly created regulatory bodies, or existing state agencies, endowed with more power to regulate and revise rules. Such policies are sold as “standards” to drive quality, but they are no more standards than requiring a teacher to be certified is a qualitative standard. Uber authorizing provisions put state agencies in control of independent authorizers, negating independence. Those same agencies then become empowered to do precisely what they are not capable of doing – deciding when and how parents should have options over what types of schools under what types of conditions. The net effect is a growth of oversight powers that are intended to police quality but end up micromanaging, and thus discouraging, the creation, growth, and advancement of independent public schools.

States that assure independence for authorizing from traditional state entities and are free from uber authorizing, score higher than those that do not. While still number one in our rankings, D.C. risks losing ground if it continues on a slow but slippery slope of allowing the city and its agencies to micromanage the authorizer’s processes. It’s also unique in that it has one authorizer that was created when the city did not have a “state” board of education, and when the city was under the control of an independent board itself from the city council. That legacy of independence is now threatened by the restoration of city structures that have begun to assert various controls over chartering in the city. The law provides for the establishment of new entities for authorizing, such as universities. Pursuing additional authorizers would allow the existing D.C. Public Charter Board to stay on its feet, and create alternative innovations for opening and managing new schools.

Scaling Up: Much focus has been put on scale in the last few years. Philanthropic dollars, research reports, and even federal policy encourages scaling up of proven practices and networks. But there is more to scaling up than expanding an already existing model of schooling. Scaling up should include the extent to which state laws permit the natural expansion of schools – whether they are single site or network – as well as the expansion of the number of schools. If only proven schools are scaled, what does that say about the notion that chartering is intended to provide for not just replication but innovation in brand new schooling ideas? After all, those who today are proven were once new and unproven.

The rankings account not only for whether a state’s law provides for growth, but whether the policy in law actually results in growth in practice.

Freedom to Operate, Freedom to Innovate: Traditionally, the National Charter School Law Rankings factor in any limitations or freedoms to operate and are awarded points based on such conditions. However, it is increasingly clear that complexities in the law are growing, and they now not only stipulate the degree to which schools are free from state and local laws, but often stipulate substantial conditions dictating not only how and when charters are created, but how they operate. States that permit innovations to be developed and adopted – innovations in curriculum, technology, structure or even the kinds of businesses or partnerships with which they engage – will yield more innovation and diversity than those that do not.

Many critics often argue that charter schools no longer look or seek to be as innovative as had been – reportedly – their intent. It was actually something much more compelling than that which brought charter schools into existence. It was the demand for parental choices for diverse learning options that did not follow the same model as the monolithic school districts. It was diversity and choice, and diversity would allow the creation of innovations. Innovation need not be something dramatic or new (indeed innovation can be doing the same thing slightly differently). The reality, in all too many instances, is that charters have been forced into the traditional education box. Thus, the freedom to innovate reflects whether a state law allows, for example, both on-ground and online or blended models, whether they can contract with all manner of educational provider, whether same-sex schools are allowed, whether there may be alternative high schools with alternative assessments attached to them, and numerous other potential innovations that neither humans or law may have yet conceived.

States that permit schools the freedom to innovate and do not prescribe conditions that look and operate like traditional public schools will rank higher than those which limit variety and innovation.

Equity – As important as being able to open and operate in a state that has multiple independent authorizers is being able to focus on the work needing to be accomplished. To do that requires funding, funding that is often woefully inadequate and often deliberately skewed to be inferior to traditional school districts. Many in the charter school advocacy world have been open to negotiating lower per-pupil dollar amounts to get a law passed, even though doing so would hamstring those schools from the start. Others ignore complex funding formulas or simple words and phrases that sound good in law but can often be widely interpreted in practice. For example, take the word “proportionate” which is in a companion funding law to Kentucky’s new below-average charter school law. Proportionate technically means relative or in measure of other things. Such terminology gives the funding authorities, in this case school districts, the authority to determine what is and isn’t proportional to all other spending categories. They can, and will, self select which funding and which amounts go to charters. Districts can narrow the amount spent per pupil. In other words, just one word sanctions arbitrary decision-making. That is why they were opposed to using the words “pro-rata” in the funding language, which would have clearly required precise, individual, equalized student funding to follow students to charters.

States are evaluated not only on both the policy and practice of operational funding statutes, but also on whether and how they fund facilities and this year, for the first time, Pre-K. If, as it should be, chartering is part of the overall education landscape and education reform efforts in this nation, funding must also be both commensurate and comprehensive.

A final word about chartering –

The debate over charter schools is now divided neatly into two camps – those who believe that accountability means there is additional oversight from centralized government entities, including state education departments and the federal government in driving start up grant funds, and those who believe that accountability is multi-dimensional, beginning with parents making choices and not being confined to conventional definitions of what works for every child.

The parent choice accountability camp also believes that data is essential to any educational enterprise and that it must be available and transparent. The role of government is to require data to be reported; it is not to require hostile government entities to parse and use the data to close schools when that data is not only easily manipulated but often misunderstood.

Raising the academic quality of charter schools is best achieved by enabling students to leave mediocre charter schools and select from higher quality nearby charter school options. The “culling of the herd”, where necessary, should result from stronger competition that enables parents to choose more effective schools, not sudden regulatory termination that dumps students back into the very public schools they were seeking to avoid (and which may be worse). In economic terms, overall quality is raised by good charter schools “crowding out” mediocre charter schools. Charter authorizers should fulfill a significant, but limited, academic accountability role of terminating or not renewing consistently, demonstrably bad schools, by documenting that the education they offer is not only not meeting students needs but that enrollment reflects such failures. Authorizers should also terminate charters for other non-academic reasons, such as safety or financial malfeasance.

To accomplish what we, along with well-known researchers and other choice advocates, agree represents a hearty charter school movement, the emphasis should be on eliminating hurdles to growth of well-managed charter schools and organizations to serve more students.

Charter regulation, approval, and oversight should be transparent, predictable, and avoid micro-management of academics, discipline, and staff hiring and termination. Regulation should be flexible enough to encourage charter schools designed to meet the needs of special populations by allowing them to meet requirements that are reasonable and appropriate for their students. And yet, it is precisely that regulation that is discouraging new charter school growth. With barely 6 percent of all public school students in charter schools nationwide, two percent growth over one year is totally unacceptable and an indication that something is amiss. Risk-averse, highly bureaucratic state and local actors are causing the stagnation. It comes not just from opponents, but from heavy-handed friends. Their heavy reliance on government to solve perceived issues of quality will bring charter schools to a screeching halt unless the policies they espouse reverse course.

We hope the 2017 updated criteria and rankings will catalyze a necessary, national and state-level debate on the most effective ways to ignite charter growth in order to increase educational options as well as achieve excellence. It is clear from the trends that real education reform does not result from local compliance with federal regulations or statewide requirements but, comes instead, school by school and classroom by classroom. It succeeds when educators work with parents at the local/institutional level to create, refine, and maintain high-performance schools that raise achievement and meet the needs of their students. Current charter requirements and policies that unnecessarily constrain charter growth and competition or deter investment need to be rethought and revised. The predictable absence of significant NAEP achievement gains in recent years in all but a handful of communities and states with the strongest laws, and the lack of consensus on what comes next, means there is an opening for fresh thinking on what constitutes education reform.

Founder & CEO

March 22, 2017