You’ve been called a “great guy” by democrats who think you will help them grow school reform. You’ve “made a lot of progress,” say university types. You’re the “compromise candidate,” because the unions have endorsed you.

You’ve been called a “great guy” by democrats who think you will help them grow school reform. You’ve “made a lot of progress,” say university types. You’re the “compromise candidate,” because the unions have endorsed you.

Now comes the hard part.

Frankly, you’re one of the few national education leaders I do not know, which gives me some rare objectivity in the matter. That, and the fact that my organization has no horse in the race, no member group to protect, no current ties to you at all.

So, let me offer some fresh advice about what you can expect – and what might take you by surprise.

1) Everyone will want to claim you as his own. Allowing them to do so will compromise your efforts.

From where you will sit just across from the Capitol building you’ll see dozens of advocates converge on your department. They’ll arrive at the invitation of career department employees, who will beckon them to provide ideas for the new Secretary. Your incoming advisors will have little control over this. The bureaucracy has a way of creating environments and momentum entirely on its own.

As these groups come and go, they will tell journalists about their sense of your department. They will say, “We’ve been told he’ll fully fund our program” or “the Secretary is working hard to ensure all three year olds eat before school.” Some might say “he’s the biggest charter school supporter we’ve ever had and he’ll show that soon.”

And the Congress, just a few blocks away, will attribute all of these comments directly to you. The solution:

• Let the hard working career pool know upon your arrival that you and the others appointed by the President are the only ones allowed to speak about policy (though, of course, you’ll consult them regularly)

•Articulate your agenda and your priorities in the first week to avoid speculation and dissension

2) The Department of Education’s most senior level staff, from the attorney general’s office to the division manager in charge of state data collection, operates differently than your staff in Chicago. They are seasoned employees who focus on implementing the law as it is written, not as it should be. Change comes slowly to them and their colleagues.

The first advice I was given when I arrived at my newly appointed post in the education department years ago was illustrative – “Things take time here,” they said. “Don’t expect to change policy overnight. It takes years.”

Yeah. Thanks. No.

You must choose two kinds of people to join you –Washington insiders who know the ropes and passionate reformers. Both types are necessary to ensure key agenda items do not get lost in an “it takes time” comfort zone.

3) Saying you are “for” charters and performance pay will not make you a national reformer.

Supporting increases in the federal grant programs for charters does not constitute a reform pedigree. Directing those funds to states where charter laws are strong – as the law requires – gives you that pedigree. Likewise, backing and pushing through Congress a performance pay plan will not make you a reformer. Using your bully pulpit to urge the unions to give up seniority and embrace comprehensive pay for performance will.

You can demonstrate how much you really do want to achieve by doing a few simple things that cost no money:

• Deliver an early “State of Education” speech, to follow the President-elect’s first major address as President. Making education the subject of the first major cabinet address after the President speaks puts the priority where it should be—at the top.

• Articulate the role of the Education Secretary versus a local superintendent, taking care to be bold about a national vision that embraces accountability and choice. Make it clear that you will expect superintendents to do their part in making such ideas flourish.

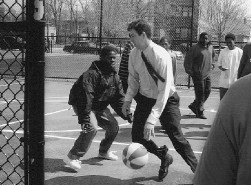

Just like on the basketball court you cherish, Washington requires skilled players who learn their opponents’ moves before they act.

We reformers look forward to the tip off as well as getting in the game, Mr. almost-Secretary.